|

|

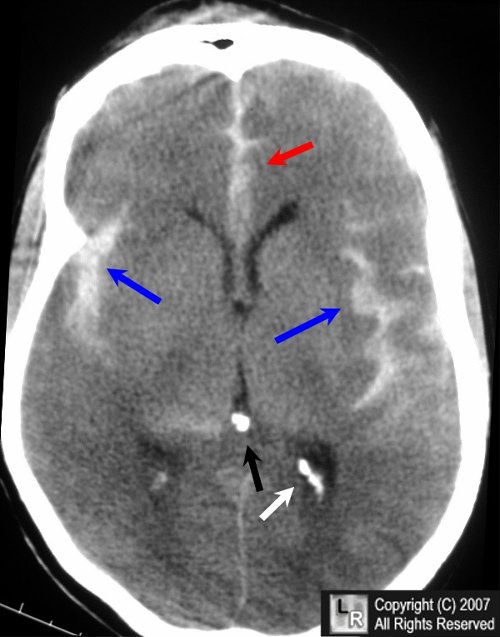

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

SAH

General Considerations

- Bleeding into the subarachnoid space, between the pia mater and the arachnoid

- Most commonly occurs between ages of 25 to 65, increasing in frequency with age

- Most common causes are rupture of an intracranial aneurysm or head trauma

Causes of SAH

- Head trauma

- Intracranial aneurysms

- Cause of approximately 80% of nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Most occur around the circle of Willis (berry aneurysm) at

- Middle cerebral artery bifurcation

- Anterior communicating artery

- Posterior communicating artery

- Also

- Ophthalmic arteries

- Vertebral and basilar arteries

- Benign perimesencephalic hemorrhage

- Blood limited to midbrain

- Less frequent causes of SAH

Risk factors

Clinical findings

- Headache is most common symptom

- Frequently reported as severe (“worst headache of life"), of abrupt onset, reaches maximum intensity within seconds (“thunderclap headache”)

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Change in mental status -- confusion

- Decreased level of consciousness including coma

- Spinal fluid may be bloody

Imaging findings

- Unenhanced CT of the brain is the study of choice for establishing presence of SAH

- Acute hemorrhage is most evident 2-3 days after the acute bleed

- CT angiography and MRA have replaced conventional angiography in most institutions for the identification and location of the aneurysm itself

- Acute hemorrhage appears as high-attenuation (white) material that fills the normally black subarachnoid spaces, which include

- The basilar cisterns

- Especially the suprasellar cistern

- The sulci

- Especially the Sylvian fissures

- Over the convexities of the brain, SAH produces white, branching densities representing the normally black sulci filled with blood

- During the subacute period (days to weeks after acute bleed), look for

- Decreased visualization of the normally “black” fluid within the sulci and basal cisterns

- Enlargement of the ventricles

- From communicating hydrocephalus

- False positives may occur by mistaking normal visualization of the falx cerebri and tentorium cerebelli for SAH

- MR angiography is useful in identifying the location of aneurysms

- Cerebral angiography is used for the detection of intracranial aneurysms

- Such features as aneurysm size and shape can help determine which aneurysm has bled

- Still considered the “gold” standard for diagnosis of intracranial aneurysm

Treatment

- Relief of associated vasospasm (occurs in as many as 50% of patients with SAH) may be accomplished medically with calcium channel blockers

- Urgent surgical removal of blood may be indicated

- Early surgical clipping is used to prevent rebleeding

- Endovascular management is also now widely used

Complications

- Acute

- Chemical meningitis from blood in subarachnoid space, increased intracranial pressure and vasospasm (“angry brain”)

- Coma

- Brainstem herniation

- Non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Myocardial ischemia or infarction

- Subacute

- Ischemia of other parts of the brain because of vasospasm

- Hyponatremia due to syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion

- Chronic

- Long-term immobility leading to

- Pneumonia

- Pulmonary embolism

- Recurrence of SAH

- Persistent neurologic deficits

Prognosis

- About 10 to 30% die before reaching medical help with first bleed

- Nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage in patients who reach the hospital still has a mortality rate of 30 to 60%

- SAH from an arteriovenous malformation has a better prognosis than SAH from a ruptured aneurysm

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). There is high-attenuation blood in the Sylvian fissures (blue arrows) and the interhemispheric fissure (red arrow) seen on this non-contrast enhanced CT of the brain. Do not confuse normal, physiologic calcifications (white and black arrows) for blood.

For additional information about this disease, click on this icon above.

For this same photo without the arrows, click here

Abner Gershon, MD, Robert Feld, MD, Michael T Twohig, MD eMedicine

|

|

|